Amazon S3 is a simple and very useful storage of binary objects (aka “files”). To use it, you create a “bucket” there with a unique name and upload your objects.

Afterwards, AWS guarantees your object will be available for download through their RESTful API.

A few years ago, AWS introduced a S3 feature called static website hosting.

With static website hosting, you simply turn on the feature and all objects in your bucket become available through public HTTP. This is an awesome feature for hosting static content, such as images, JavaScript files, video and audio content.

When using the hosting, you need to change the CNAME record in your DNS so that it points to www.example.com.aws.amazon.com. After changing the DNS entry, your static website is available at www.example.com just as it would be normally.

When using Amazon S3, though, it is not possible to protect your website because the content is purely static. This means you can’t have a login page on the front end. With the service, you can either make your objects either absolutely public—so that anyone can see them online—or assign access rights to them—but only for users connected through RESTful API.

My use case with the service was a bit more complex, though. I wanted to host my static content as S3 objects. However, I wanted to do this while ensuring only a few people had access to the content using their Web browsers.

HTTP Basic Authentication

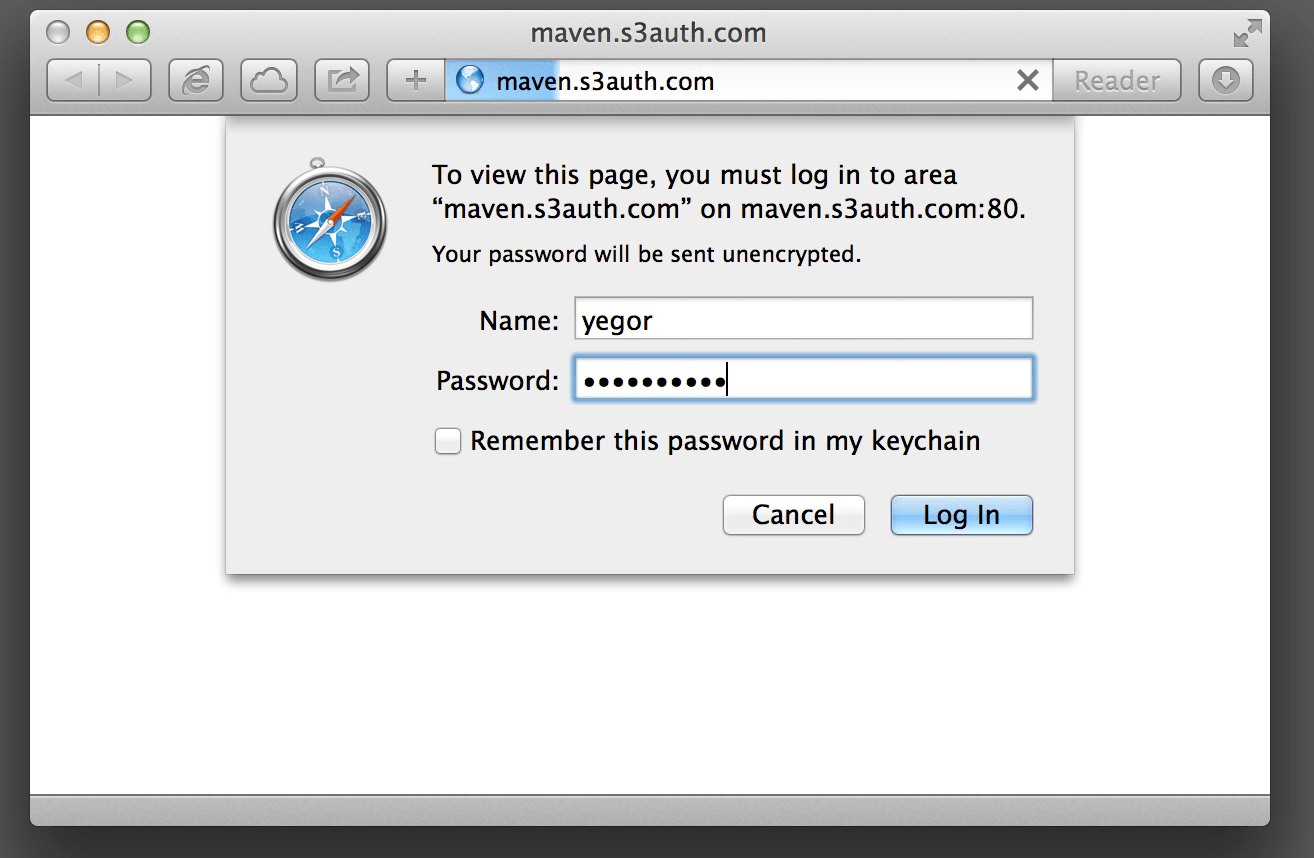

The HTTP protocol offers a nice “basic access authentication” feature that doesn’t require any extra site pages.

When an HTTP request arrives at the server, it doesn’t deliver the content but replies with a 401 status response. This response means literally “I don’t know who you are, please authenticate yourself.”

The browser shows its native login screen and prompts for a user name and password. After entering the login credentials, they are concatenated, Base64 encoded, and added to the next request in Authorization HTTP header.

Now, the browser tries to make another attempt to fetch the same webpage. But, this time, the HTTP request contains a header:

Authorization: Basic am9lOnNlY3JldA==

The above is just an example. In the example, the Base64 encoded part means joe:secret, where joe is the user name and secret the password entered by the user.

This time the server has authentication information and can make a decision whether this user is authenticated (his password matches the server’s records) and authorized (he has permission to access the request webpage).

s3auth.com

Since Amazon doesn’t provide this feature, I decided to create a simple web service, s3auth.com, which stays in front of my Amazon S3 buckets and implements the HTTP-native authentication and authorization mechanism.

Instead of making my objects public, though, I make them private and point my CNAME record to relay.s3auth.com. HTTP requests from Web browsers then arrive at my server, connect to Amazon S3, retrieve my objects and deliver them back in HTTP responses.

The server implements authentication and authorization using a special file .htpasswd in the root of my bucket. The format of the .htpasswd file is identical to the one used by Apache HTTP Server—one user per line. Every line has the name of a user and a hash version of his password.

Implementation

I made this software open source mostly to guarantee to my users that the server doesn’t store their private data anywhere, but rather acts only as a pass-through service. As a result, the software is on GitHub.

For the sake of privacy and convenience, I use only OAuth2 for user accounts. This means that I don’t know who my users are. I don’t possess their names or emails, but only their account numbers in Facebook, Google Plus or GitHub. Of course, I can find their names using these numbers, but this information is public anyway.

The server is implemented in Java6. For its hosting, I’m using a single Amazon EC2 m1.small Ubuntu server. These days, the server seems to work properly and is stable.

Extra Features

Besides authentication and authorization, the s3auth.com server can render lists of pages—just like Apache HTTP Server. If you have a collection of objects in your bucket—but the index.html file is missing—Amazon S3 delivers a “page not found” result. Conversely, my server displays a list of objects in the bucket, when no index.html is present, and makes it possible to navigate up or down one folder.

When your bucket has the versioning feature turned on, you are able to list all versions of any object in the browser. To do this, just add ?all-versions to the end of the URL to display the list. Next, click a version to have s3auth.com retrieve and render it.

Traction

I created this service mostly for myself, but apparently I’m not the only with the problems described above. At the moment, s3auth.com hosts over 300 domains and sends through more than 10Mb of data each hour.

PS. This post explains how s3auth.com can be used as a front-end to your Maven repository: How to Set Up a Private Maven Repository in Amazon S3.