I often hear this argument against immutable objects: “Yes, they are useful when the state doesn’t change. However, in our case, we deal with frequently changing objects. We simply can’t afford to create a new document every time we just need to change its title.” Here is where I disagree: object title is not a state of a document, if you need to change it frequently. Instead, it is a document’s behavior. A document can and must be immutable, if it is a good object, even when its title is changed frequently. Let me explain how.

Identity, State, and Behavior

Basically, there are three elements in every object: identity, state, and behavior. Identity is what distinguishes our document from other objects, state is what a document knows about itself (a.k.a. “encapsulated knowledge”), and behavior is what a document can do for us on request. For example, this is a mutable document:

class Document {

private int id;

private String title;

Document(int id) {

this.id = id;

}

public String getTitle() {

return this.title;

}

public String setTitle(String text) {

this.title = text;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format("doc #%d about '%s'", this.id, this.text);

}

}

Let’s try to use this mutable object:

Document first = new Document(50);

first.setTitle("How to grill a sandwich");

Document second = new Document(50);

second.setTitle("How to grill a sandwich");

if (first.equals(second)) { // FALSE

System.out.println(

String.format("%s is equal to %s", first, second)

);

}

Here, we’re creating two objects and then modifying their encapsulated states. Obviously, first.equals(second) will return false because the two objects have different identities, even though they encapsulate the same state.

Method toString() exposes the document’s behavior—the document can convert itself to a string.

In order to modify a document’s title, we just call its setTitle() once again:

first.setTitle("How to cook pasta");

Simply put, we can reuse the object many times, modifying its internal state. It is fast and convenient, isn’t it? Fast, yes. Convenient, not really. Read on.

Immutable Objects Have No Identity

As I’ve mentioned before, immutability is one of the virtues of a good object, and a very important one. A good object is immutable, and good software contains only immutable objects. The main difference between immutable and mutable objects is that an immutable one doesn’t have an identity and its state never changes. Here is an immutable variant of the same document:

@Immutable

class Document {

private final int id;

private final String title;

Document(int id, String text) {

this.id = id;

this.title = text;

}

public String title() {

return this.title;

}

public Document title(String text) {

return new Document(this.id, text);

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object doc) {

return doc instanceof Document

&& Document.class.cast(doc).id == this.id

&& Document.class.cast(doc).title.equals(this.title);

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format(

"doc #%d about '%s'", this.id, this.text

);

}

}

This document is immutable, and its state (id ad title) is its identity. Let’s see how we can use this immutable class (by the way, I’m using @Immutable annotation from jcabi-aspects):

Document first = new Document(50, "How to grill a sandwich");

Document second = new Document(50, "How to grill a sandwich");

if (first.equals(second)) { // TRUE

System.out.println(

String.format("%s is equal to %s", first, second)

);

}

We can’t modify a document any more. When we need to change the title, we have to create a new document:

Document first = new Document(50, "How to grill a sandwich");

first = first.title("How to cook pasta");

Every time we want to modify its encapsulated state, we have to modify its identity too, because there is no identity. State is the identity. Look at the code of the equals() method above—it compares documents by their IDs and titles. Now ID+title of a document is its identity!

What About Frequent Changes?

Now I’m getting to the question we started with: What about performance and convenience? We don’t want to change the entire document every time we have to modify its title. If the document is big enough, that would be a huge obligation. Moreover, if an immutable object encapsulates other immutable objects, we have to change the entire hierarchy when modifying even a single string in one of them.

The answer is simple. A document’s title should not be part of its state. Instead, the title should be its behavior. For example, consider this:

@Immutable

class Document {

private final int id;

Document(int id) {

this.id = id;

}

public String title() {

// read title from storage

}

public void title(String text) {

// save text to storage

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object doc) {

return doc instanceof Document

&& Document.class.cast(doc).id == this.id;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format("doc #%d about '%s'", this.id, this.title());

}

}

Conceptually speaking, this document is acting as a proxy of a real-life document that has a title stored somewhere—in a file, for example. This is what a good object should do—be a proxy of a real-life entity. The document exposes two features: reading the title and saving the title. Here is how its interface would look like:

@Immutable

interface Document {

String title();

void title(String text);

}

title() reads the title of the document and returns it as a String, and title(String) saves it back into the document. Imagine a real paper document with a title. You ask an object to read that title from the paper or to erase an existing one and write new text over it. This paper is a “copy” utilized in these methods.

Now we can make frequent changes to the immutable document, and the document stays the same. It doesn’t stop being immutable, since it’s state (id) is not changed. It is the same document, even though we change its title, because the title is not a state of the document. It is something in the real world, outside of the document. The document is just a proxy between us and that “something.” Reading and writing the title are behaviors of the document, not its state.

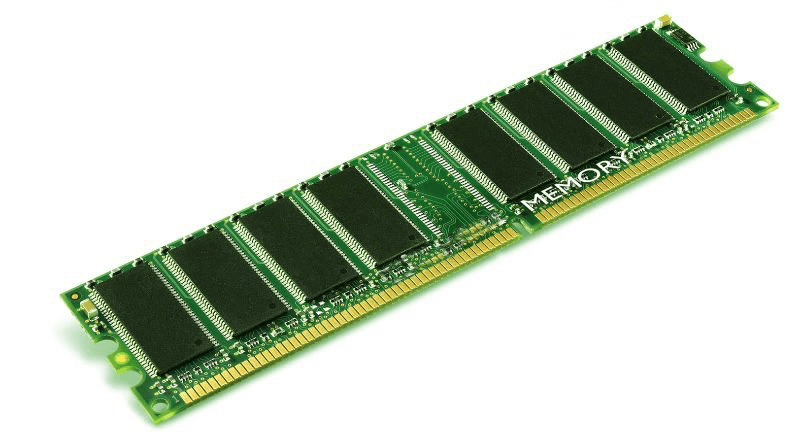

Mutable Memory

The only question we still have unanswered is what is that “copy” and what happens if we need to keep the title of the document in memory?

Let’s look at it from an “object thinking” point of view. We have a document object, which is supposed to represent a real-life entity in an object-oriented world. If such an entity is a file, we can easily implement title() methods. If such an entity is an Amazon S3 object, we also implement title reading and writing methods easily, keeping the object immutable. If such an entity is an HTTP page, we have no issues in the implementation of title reading or writing, keeping the object immutable. We have no issues as long as a real-world document exists and has its own identity. Our title reading and writing methods will communicate with that real-world document and extract or update its title.

Problems arise when such an entity doesn’t exist in a real world. In that case, we need to create a mutable object property called title, read it via title(), and modify it via title(String). But an object is immutable, so we can’t have a mutable property in it—by definition! What do we do?

Think.

How could it be that our object doesn’t represent a real-world entity? Remember, the real world is everything around the living environment of an object. Is it possible that an object doesn’t represent anyone and acts on its own? No, it’s not possible. Every object is a representative of a real-world entity. So, who does it represent if we want to keep title inside it and we don’t have any file or HTTP page behind the object?

It represents computer memory.

The title of immutable document #50, “How to grill a sandwich,” is stored in the memory, taking up 23 bytes of space. The document should know where those bytes are stored, and it should be able to read them and replace them with something else. Those 23 bytes are the real-world entity that the object represents. The bytes have nothing to do with the state of the object. They are a mutable real-world entity, similar to a file, HTTP page, or an Amazon S3 object.

Unfortunately, Java (and many other modern languages) do not allow direct access to computer memory. This is how we would design our class if such direct access was possible:

@Immutable

class Document {

private final int id;

private final Memory memory;

Document(int id) {

this.id = id;

this.memory = new Memory();

}

public String title() {

return new String(this.memory.read());

}

public void title(String text) {

this.memory.write(text.getBytes());

}

}

That Memory class would be implemented by JDK natively, and all other classes would be immutable. The class Memory would have direct access to the memory heap and would be responsible for malloc and free operations on the operating system level. Having such a class would allow us to make all Java classes immutable, including StringBuffer, ByteArrayOutputStream, etc.

The Memory class would explicitly emphasize the mission of an object in a software program, which is to be a data animator. An object is not holding data; it is animating it. The data exists somewhere, and it is anemic, static, motionless, stationary, etc. The data is dead while the object is alive. The role of an object is to make a piece of data alive, to animate it but not to become a piece of data. An object needs some knowledge in order to gain access to that dead piece of data. An object may need a database unique key, an HTTP address, a file name, or a memory address in order to find the data and animate it. But an object should never think of itself as data.

What Is the Practical Solution?

Unfortunately, we don’t have such a memory-representing class in Java, Ruby, JavaScript, Python, PHP, and many other high-level languages. It looks like language designers didn’t get the idea of alive objects vs. dead data, which is sad. We’re forced to mix data with object states using the same language constructs: object variables and properties. Maybe someday we’ll have that Memory class in Java and other languages, but until then, we have a few options.

Use C++. In C++ and similar low-level languages, it is possible to access memory directly and deal with in-memory data the same way we deal with in-file or in-HTTP data. In C++, we can create that Memory class and use it exactly the way we explained above.

Use Arrays. In Java, an array is a data structure with a unique property—it can be modified while being declared as final. You can use an array of bytes as a mutable data structure inside an immutable object. It’s a surrogate solution that conceptually resembles the Memory class but is much more primitive.

Avoid In-Memory Data. Try to avoid in-memory data as much as possible. In some domains, it is easy to do; for example, in web apps, file processing, I/O adapters, etc. However, in other domains, it is much easier said than done. For example, in games, data manipulation algorithms, and GUI, most of the objects animate in-memory data mostly because memory is the only resource they have. In that case, without the Memory class, you end up with mutable objects :( There is no workaround.

To summarize, don’t forget that an object is an animator of data. It is using its encapsulated knowledge in order to reach the data. No matter where the data is stored—in a file, in HTTP, or in memory—it is conceptually very different from an object state, even though they may look very similar.

A good object is an immutable animator of mutable data. Even though it is immutable and data is mutable, it is alive and data is dead in the scope of the object’s living environment.