In this post, I’ll try to walk you through a project managed with the spirit of Puzzle Driven Development (PDD). As I do this, I will attempt to convey typical points of view of various project members.

Basically, there are a few key roles in any software team:

- Project Manager—assigns tasks and pays on completion

- System Analyst—documents the product owner’s ideas

- Architect—defines how system components interact

- Designer—implements most complex components

- Programmer—implements all components

- Tester—finds and reports bugs

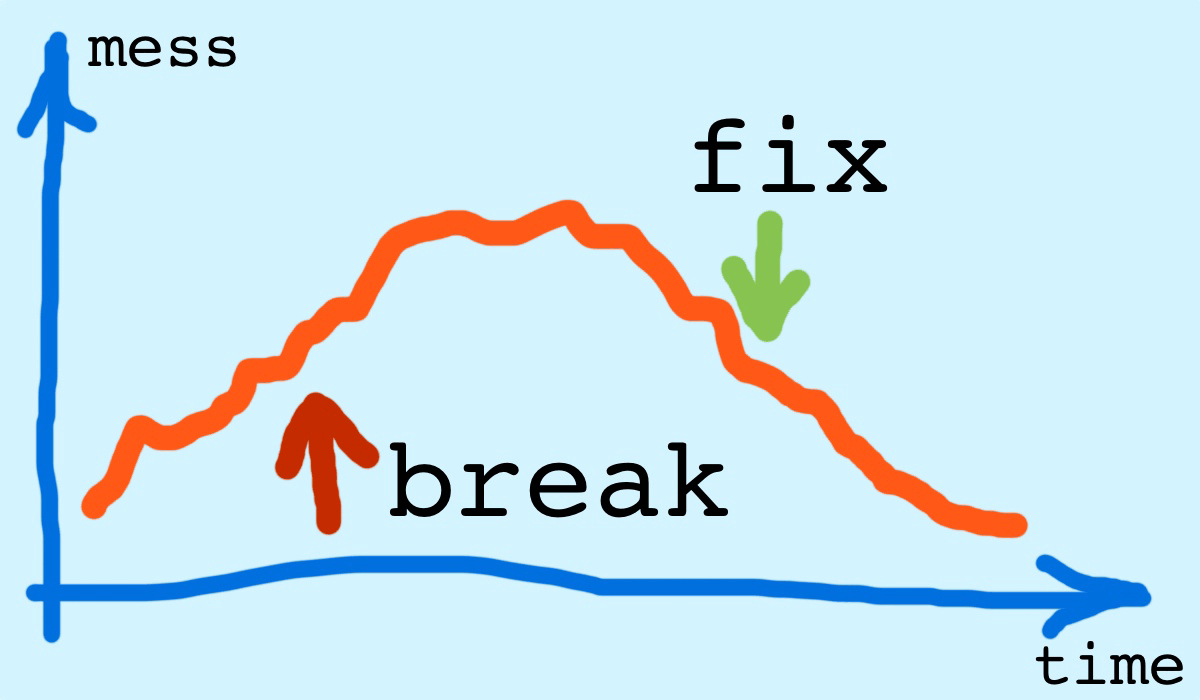

Everybody, except the project manager, affects the project in two ways: they fix it and they break it at the same time. Let me explain this with a simple example.

Fix and Break

Let’s assume, for the sake of simplicity, that a project is a simple software tool written by me for a close friend. I created the first draft version 0.0.1 and delivered it to him. For me, the project is done. I’ve completed the work, and hopefully will never have to return to it again.

However, the reality of the project is very different. In just a few hours, I receive a call from my friend saying that a he’s found a few bugs in the tool. He is asking me to fix them. Now, I can see that the project is not done. In fact, it’s broken. It has a few bugs in it, which means a few tasks to complete.

I’m going to fix the project, by removing the bugs. I implement a new version of the software, name it 0.0.2 and ship it to my friend. Again, I believe my project is finished. It is fixed and should be closed.

This scenario repeats itself again and again until my friend stops calling me. In other words, until he stops breaking my project.

It is obvious that the more my friend breaks my project, the higher the quality of the software delivered ultimately at the end. Version 0.0.1 was just a very preliminary version, although I considered it final at the time I released it. In a few months, after I learn of and fix hundreds of bugs, version 3.5.17 will be much more mature and stable.

This is the result of this “fix and break” approach.

The diagram shows the relation between time and mess in the project. The bugs my friend is reporting to me are breaking the project, increasing its instability (or simply its messiness). New versions I release resolve the bugs and are fixing the project. Your GitHub commit dynamics should resemble this graph, for example:

When the project starts, its messiness is rather low, and then it starts to grow. The messiness then reaches its peak and starts to go down.

Project Manager

The job of a project manager is to do as much as possible to fix the project. He has to use the sponsor’s time and money in order to remove all bugs and inconsistencies and return the project back to a “fixed” state.

When I say “bugs,” I mean more than just software errors but also:

- unclear or ambiguous requirements

- features not yet implemented

- functional and non-functional bugs

- lack of test coverage

- unresolved

@todomarkers - lack of risk analysis

- etc.

The project manager gives me tasks that he wants done in order to fix and stabilize the project to return it back to a bug-free state.

My job, as a member of a software team, is to help him perform the needed fixes and, at the same time, do my best to break the project! In the example with my friend, he was breaking the project constantly by reporting bugs to me. This is how he helped both of us increase the final quality of the product.

I should do the same and always try to report new bugs when I’m working on some feature. I should fix and break at the same time.

Now let’s take a closer look at project roles.

System Analyst

A product owner submits an informal feature request, which usually starts with “it would be nice to have…” I’m a system analyst and my job is to translate owner’s English into formal specifications in the SRS, understandable both by programmers and myself. It’s not my responsibility to implement the feature.

My task is complete when a new version of the SRS is signed by the Change Control Board. I’m an interpreter for the product owners, translating from their language to formal language needed in the SRS document. My only customer is the product owner. As soon as she closes the feature request, I’ll be paid.

Besides feature requests from product owners, I often receive complaints about the quality of the SRS. The document may not be clear enough for some team members. Therefore, it’s my job to resolve clarity problems and fix the SRS. These team members are also my customers. When they close their bug reports, I’ll be paid.

In both cases (a feature request or a bug,) I can make changes to the SRS immediately - if I have enough time. However, it’s not always possible. I can submit a bug and wait for its resolution; but, I don’t want to keep my customers waiting.

This is where puzzle driven development helps me. Instead of submitting bug reports, I add “TBD” puzzles in the SRS document. The puzzles are informal replacements of normally very strict formal requirements. They satisfy my customer, since they are in plain English, and are understandable by technical people.

Thus, when I don’t have time, I don’t wait. I change the SRS using TBD-s at points where I can’t create a proper and formal description of the requirements or simply don’t know what to write exactly.

Architect

Now, I’m the architect, and my task is to implement a requirement, which has been formally specified in the SRS. PM is expecting a working feature from me, which I can deliver only when the architecture is clear and classes have been designed and implemented.

Being an architect, I’m responsible for assembling all of the components together and making sure they fit. In most cases, I’m not creating them myself, but I’m telling everybody how they should be created. My work flow of artifacts is the following:

I receive requirements from the SRS, produce UML diagrams and explain to designers how to create source code according to my diagrams. I don’t really care how source code is implemented. I’m more concerned with the interaction of components and how well the entire architecture satisfies functional and non-functional (!) requirements.

My task will be closed and paid when the system analyst changes its state to “implemented” in the SRS. The system analyst is my only customer. I have to sell my solution to him. Project manager will close my task and pay me when system analyst changes the status of the functional requirement from “specified” to “implemented.”

The task sounds big, and I have only half an hour. Obviously, puzzle driven development should help me. I will create many tickets and puzzles. For example:

- SRS doesn’t explain requirements properly

- Non-functional requirements are not clear

- UML diagrams are not clear enough

- Components are not implemented

- Build is not automated

- Continuous integration is not configured

- Quality of code is not under control

- Performance testing is not automated

When all of my puzzles are resolved, I can get back to my main task and finish feature implementation. Obviously, this may take a long time - days or even weeks.

But, the time cost of the main task is less than an hour. What is the point of all this hard work? Well, it’s simple; I’ll earn my hours from all the bugs reported. From this small half-an-hour task, I will generate many tickets, and every one of them will give me extra cash.

Designer and Programmer

The only real differences between designer and programmer are the complexity of their respective tasks and the hourly rates they receive. Designers usually do more complex and higher level implementations, while programmers implement all low-level details.

I’m a programmer and my task is to implement a class or method or to fix some functional bug. In most cases, I have only half an hour available. And, most tasks are bigger and require more time than that.

Puzzle driven development helps me break my task into smaller sub-tasks. I always start with a unit test. In the unit test, I’m trying to reproduce a bug or model the feature. When my test fails, I commit it and determine the amount of time I have left. If I still have time to make it pass—I do it, commit the changes and report to the project manager.

If I don’t have time to implement the fix, I mark pieces of code that don’t already have @todo markers, commit them and report to the project manager that I’ve finished.

As you see, I’m fixing the code and breaking it at the same time. I’m fixing it with my new unit test, but breaking it with @todo puzzles.

This is how I help to increase the overall quality of the project - by fixing and breaking at the same time.

Tester

I’m a tester and my primary motivation is to find bugs. This may be contradictory to what you’ve heard before; but in XDSD, we plan to find a certain amount of bugs at every stage of the project.

As as a tester, I receive tasks from my project manager. These tasks usually resemble “review feature X and find 10 bugs in it.” The project manager needs a certain number of bugs to be found in order to fix the project. From his point of view, the project is fixed when, say, 200 bugs have been found. That’s why he asks me to find more.

Thus, to respond to the request, i find bugs to do my part in regard to the “fixing” part of the bigger picture. At the same time, though, I can find defects on my own and report them. This is the “breaking” part of my mission.